शमशान की भीड़

The Crowded Crematorium

मँझोला क़द, गेहूँआ रंग, चेहरे पर झुर्रियाँ और अधेड़ उम्र वाला शख़्स है प्रकाश । दिखने में एकदम तंदरुस्त, थोड़े मोटे मानो डोरीमोन जैसी आँखों पर गोल चश्मा लगाए,जिसे कुछ देर बाद साफ़ करने बैठ जाता, क्योंकि मुँह पर लगाए मास्क के कारण बार-बार चश्मे पर भाप इकट्ठी हो जाती जिससे उन्हें धुँधला दिखने लगता।

Prakash’s face is creased with age. He is dusky skinned, middle aged and of medium built. He looks like Doremon, with his round spectacles which have to be constantly cleaned as they become clouded when he breathes through the mask fixed around his mouth and nose.

प्रकाश की दुकान शमशान घाट के खुलने से पहले ही खुल जाती है। यानी शमशान घाट का समय जहाँ सुबह दस बजे का है तो उनकी दुकान आठ बजे ही खुल जाती है। चिताओं के जलने से वहाँ लगातार गर्मी रहती थी। और ये जून-जुलाई का महीना था, इस समय आसमान से मानो आग बरसती थी।

Prakash’s shop opens well before the opening time of the crematorium nearby. The crematorium opens at ten but Prakash’s shop opens by eight, every morning. The burning of corpses would keep the area constantly smouldering and intensely hot and now in the months of June-July it seemed that even the skies were showering embers.

कोरोना के इन दिनों में शमशान के पासवाले घरों में रहना और बाहर निकलना बेहद मुश्किल हो गया था। लोग बीमारियों की चपेट में आने लगे थे। कईयों को तो सांस लेना भी दुश्वार हो गया था।लगातार शवों के जलने के कारण लोगों ने अपने घरों का दरवाजा तक खोलना बंद कर दिया था। वे अपनी-अपनी खिड़कियों पर पर्दे या पुराने कपड़े लगा दिए थे,ताकि जलती शवों के धुएँ में लिपटी गंध उनके पास न पहुँचे। लेकिन ये करने के बावजूद भी उन्हें घुटन का सामना करना पड़ रहा था। जिसमें शामिल थे प्रकाश जी।

During these days of Corona, living close to the crematorium had become unbearable. People were dying due to sickness. Some found it difficult to breathe the air coming from the crematorium. Residents of the area keep their doors shut. Windows were covered with curtains or old sheets so that the smoke and smell of the burning bodies don’t engulf their homes. But even then, they were feeling suffocated. Prakash was one of them.

प्रकाश के लिए भी ये करना इतना आसान नहीं था। वह अपनी दुकान का दरवाजा भी बंद नहीं कर सकता था, परदे नहीं लगा सकता था। उसे तो अपनी दुकान खोल कर ही रखना था। इसी से उसका घर चलता था। उसके एक तरह चिताओं की जलती आग थी, और दूसरी तरफ़ आसमान से बरसती आग। उसे उसके बीच रहना ही था, एक टेबल फैन के सहारे दुकान चलानी थी।

This was not easy for Prakash. He could not close the doors of his shop or curtain it. His shop had to remain open because it was his source of livelihood. He was sandwiched between burning corpses and the smouldering skies. He had to survive there with a table fan for some respite.

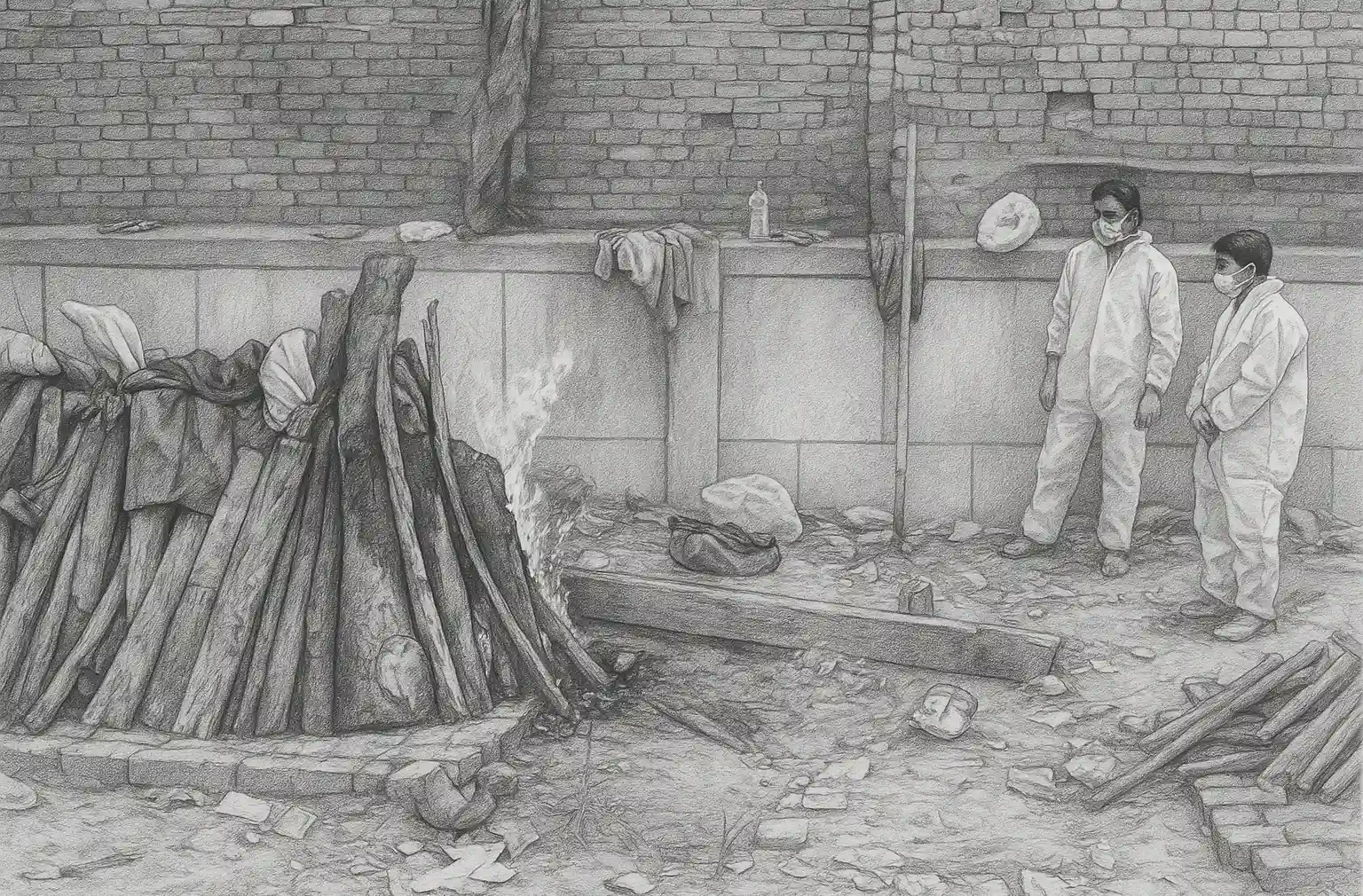

वैसे उन दिनों दाहकर्म की सामग्री बेचने वाले प्रकाश का काम ज़ोरों पर था, जब दूसरे लॉकडाउन में मौतों का सिलसिला रुकने का नाम नहीं ले रहा था। शुरुआती दौर में शमशान की लकड़ियों के ढेर दो मंजिलें मकान ऊँचे थे, जो तुरंत ही लाशों के साथ राख बन जाते। लकड़ियों की कमी हो जाने के कारण अब दो–तीन शवों को इकट्ठा ही जलाना पड़ रहा था। इस तरह तो वो शमशान कम ज्वालामुखी का इलाका ज्यादा लगता। पूरा शमशान उस बेरहम गर्मी में आग की गर्मी से बुरी तरह से तप रहा था। इस वक़्त शवों को जलाने से पहले क्रियाकर्म की तैयारी नहीं होती बल्कि जेहन में ये था कि बस शव जल्दी से जल्दी जला दिए जाए। शवों के बेहिसाब बढ़ने से कुछ शवों को पूरी तरह से जलने भी नहीं दिया गया। जिसके कारण प्रकाश जी रोज़ाना कई तरह की लाशों को जलते देखने के आदि हो चुके थे।

During the second lockdown, the death toll rose rapidly and alongside, Prakash’s work of selling all that was needed for a ritual cremation was also in high demand. The pile of wood needed for cremation was as high as a two-story house but would turn to ashes quickly as more and more bodies were cremated. As the availability of wood diminished, often two or more bodies were cremated together on the same pyre. In the summer heat, the crematorium had begun resembling a live, searing inferno. At that time, the focus was not so much on following all the rites and rituals, rather a quick cremation was what people cared about. As the number of dead bodies grew, some were not even cremated entirely. Prakash had become numb to seeing burning corpses of all kinds.

उनकी दुकान पैंतीस साल पुरानी थी। उस वक़्त वो अपने पिता के साथ हाथ बँटाया करते थे जब उन्होंने सामग्री बनाना सीखा। समझदार होने की वजह से केवल दो-चार महीने में ही वो दुकान संभालना सीख गए। दस साल की उम्र में ही उसने अपने पिता के साथ सुबह छह बजे उठना, दुकान पर बैठनाऔर ग्राहक के आने पर अर्थी की सामग्री देना-अपनी रोज़ना की ज़िंदगी में शामिल कर लिया। अक्सर जैसे ही शाम ढलने को होती वह अँधेरा होता देख अर्थी की सामग्री को अंदर रखना शुरू कर देता था। पर इस बार सबकुछ अजीब हो गया। यूँ तो रोज़ाना की ज़िंदगी में हर बार शव सिर्फ़ छह बजे तक श्मशान के दरवाज़े आता पर आज श्मशान पर भीड़ ख़त्म होने का नाम ही नहीं ले रही थी।

Prakash’s establishment was thirty-five years old. He began working alongside his father when he was very young. That is when he learnt how to put together the ritual ingredients for cremation. He learnt to manage the shop quickly. Waking up at six, sitting at the shop with his father and handing over the ritual ingredients to customers, had become a part of his life since he was ten years old. As dusk fell, Prakash would start carrying indoors, all the things on display outside his shop. But now, time had become dislocated. Usually, dead bodies were brought to the crematorium doors only until six in the evening. During these times of corona, it seemed that the rush would never end.

दक्षिणपुरी में यह एक अकेली ऐसी दुकान थी जो शव सामग्री बेचती थी। अकेली दुकान होने के कारण मुनाफ़ा भी बहुत था लेकिन लगातार मौतों के बढ़ने से उसकी दाह सामग्री भी ख़त्म होती जा रही थी। वह कहीं से भी काफ़ी कोशिश करने के बावज़ूद सामान नहीं जुटा पा रहा था। जहाँ से वह थोक सामान लाता था वह दुकान भी लॉकडाउन के कारण बंद हो गई। ऐसे में प्रकाश को अपने पुराने दोस्त मोहन कुमार की याद आई जिसकी मदनगिरी में बहुत बड़ी दाह सामग्री की दुकान है। वो अक्सर किसी भी परेशानी में कहीं से भी सामान ले ही आता था। उसने मोहन कुमार को फ़ोन किया और सामान मँगवा लिया।

Prakash’s shop was one of its kind in Dakshinpuri, and the profit of the business had risen exponentially. But the growing need for cremation ingredients had also led to a scarcity. In spite of trying many different sources, Prakash was finding it difficult to source the materials he needed. The wholesale supplier for his shop had been shut because of the lockdown. At this moment, Prakash thought of Mohan Kumar, who owned a similar though bigger shop in Madangiri. Whenever he fell short, he would approach Mohan for the things he needed. This time also he reached out to Mohan and got the items which were out of stock.

प्रकाश पंद्रह सौ के हिसाब से सामान बेचता था। बाक़ी अगर कुछ ज़्यादा या दुगुना चाहिए होता तो उसका अलग हिसाब होता। सामान में- एक मिट्टी का घड़ा, सफ़ेद चादर, फूल, सामग्री का एक नीला, हरा, लाल रंग का पैकेट, पतली भूरे रंग की एक रस्सी का गुच्छा, रुई का पैकेट, सरसों के तेल की बोतल, घी का डब्बा शामिल था।

प्रकाश की दुकान सड़क के किनारे से ही शुरू हो जाती थी। वहीं कोने पर उसने चमकती पन्नी से सजी-धजी अर्थी, डंडों के सहारे टाँग रखी थी; ताकि जो लोग प्रकाश की दुकान से परिचित नहीं हैं उन्हें दुकान का एक निशान मिल जाए।

Prakash sold a complete package of ritual ingredients and objects for fifteen hundred Rupees. If people needed anything more then he would charge extra for it. The standard package consisted of an earthenware pot, a plain white cotton sheet, small pouches of ritual material in colour coded packets of blue, green and red, a small bundle of brown coloured twine, a packet of cotton, a bottle of mustard oil and a jar of clarified butter (ghee). Prakash’s shop was at the corner of the street. He had decorated the outside of his shop with colourfully wrapped funeral frames so that people who did not know his shop would immediately recognise what he sold.

एक छोटा-सा टीवी एक छोटी टेबल पर रखा हुआ था। सामान रखने के लिए नीले रंग की अलमीरा थी। उसमें लगे पारदर्शी काँच के सहारे अंदर रखे सफ़ेद कोरे कपड़े दिख रहे थे। बाक़ी कुछ सामान कमरे में बने छोटे-छोटे खानों में फिट था। जैसे एक खाना रुई का तो दूसरा पतली रस्सी का। दो दाह सामग्री के पैकेट छोटे खाने में रखे होते, घी के डब्बों का एक अलग खाना, अगरबत्ती व धूपबत्ती के पैकेट भी एक कोनेवाले खाने में इकट्ठा रखा था। थोड़ा अंदर देखने पर तीन-चार बड़े-बड़े कार्टन दिखते जिसमें अर्थी सामग्री का एक्स्ट्रा सामान रखा रहता। दो छोटी दराज़ में पैसे।

A small television was kept on a corner table. A blue cupboard contained most of his ware. The glass doors of the cupboard revealed the neatly kept bolts of white cotton sheets. Other materials of his trade were carefully displayed on shelves spread throughout the store. One shelf for cotton wool and one for the brown twine. A separate shelf for the jars of ghee and another for different kinds of incense. Tucked away towards the back of the store, Prakash had stored cartons of extra material and the two specially marked drawers for cash.

क्रियाकर्म के मटके एक के ऊपर एक क़तार में रखे हुए थे। पाँच-छह अर्थी की सीढ़ी भी ऐसे ही एक के ऊपर एक रखी थी। और सबसे ऊपर थी वो चमकीली अर्थी जिस पर उन बुजुर्गों को धूमधाम व हँसी-खुशी से ले जाया जाता जिसने अपनी दो पीढ़ियाँ देख ली थी। आज प्रकाश सुबह-सुबह छह बजे से ही बाँस की अर्थी की जोड़ने लगा। उसके हाथों में इतनी सफ़ाई है कि एकदम चारों तरफ़ से कस कर और काफी रफ़्तार के साथ बाँस की अर्थी तैयार होती। उसने वहीं दूसरी तरफ़ टीवी भी चालू कर रखा था जहाँ दिख रहा है कि मौत के आँकड़े बढ़ते जा रहे हैं। वहीं प्रकाश की अर्थी बनाने की रफ़्तार भी बढ़ती जा रही थी। सायँ-सायँ करती सायरन बजाती एंबुलेंस जब सड़कों से गुजरती तो प्रकाश के चेहरे पर काम को लेकर हड़बड़ी के भाव आ जाते।

The earthen pots to be used for the last rites were arranged one on top of the other. The centre piece of the store was a bamboo byre wrapped in shiny strips of plastic. This special byre was used to carry the aged, who had lived a full life and seen the birth of many generations. They were carried with great celebration and joy on these brightly shining byres for their last journey.

प्रकाश की दुकान पर अब लोग आने शुरू हो गए। एक के बाद एक बंदा ऑर्डर देकर चला जाता। लोगों के स्वभाव से ही पता चल जाता था कि उनका कोई क़रीबी गया है या कोई दूर का रिश्तेदार तभी प्रकाश की दुकान पर एक आदमी आया। पैरों में चप्पल और पजामे के साथ एक हल्की-सी टी-शर्ट। उसके मुँह पर नाक तक चढ़ा मास्क और हाथ में एक रुमाल जिससे वो अपनी नम आँखों को बार-बार पोंछे जा रहा था। एक पल के लिए उसने अपने आँसू रोक भारी आवाज़ में कहा -‘भईया अर्थी का सामग्री का सामान चाहिए।’ ये बोल वो फिर से आँसू पोंछने लगा। प्रकाश उसे देख कुछ देर शांत रहे और फिर बोले-‘अरे भाईसाहब रोइए मत, एक न एक दिन हम सभी को जाना ही है।

Today Prakash had started organising a byre at six in the morning. By now, he was skilled and made them with great efficiency. The television announced the growing numbers of the dead even as he worked. With every passing ambulance siren, Prakash quickened his pace of work. As day broke, people started visiting his shop. They would place their orders and leave. Prakash could make out if people had lost someone close from the way they placed their order. A man wearing a pyjama, a light cotton t-shirt and slippers entered his store. He had a mask which covered both his mouth and nose. He kept dabbing his tears with a small handkerchief. He tried to stop the tears streaming down his face and asked in a grim voice for a package for cremation ingredients. But his tears started flowing again. Prakash looked at the man for a while and then said, “Brother please don’t cry. We all have to depart one day or the other.”

प्रकाश ने दाह संस्कार का सारा सामान पैक कर उन्हें पोटली पकड़ा दी और कहा- ‘भईया आपके पंद्रह सौ रुपये हो गए।’ उस आदमी ने जेब से पैसे निकाले और प्रकाश को देकर वहाँ से चुपचाप आँखों पर रुमाल फेरता हुआ चला गया।

Prakash packed all the things needed for the cremation, handed them over and said, “brother you have to pay fifteen hundred rupees.” The man quietly took out the money from the pocket, paid Prakash and left the shop still dabbing his eyes with his handkerchief.

आज पंद्रह शवों के लिए दाह-सामग्री की बिक्री हुई। बाईस हजार पाँच सौ रूपये आए थे। पिछले दिन उन्नीस हजार थी, उससे पहले पंद्रह हजार की बिक्री हुई थी। ये कमाई रोजाना से अलग थी। कोरोना से पहले जहाँ अमूमन दिन के तीन हजार तो कभी पंद्रह सो का समान बिकता था। उन दिनों में कभी एक तो कभी दो ही शव आते थे। महिना होते-होते चालीस हजार तक का समान बिक जाता था। समान निकालकर और जगह का किराया देकर, अंत में पच्चीस हजार तक बचते थे। वहीं इतना तो उन्होंने एक ही दिन में कमा लिया था। कमाई तो अच्छी थी पर आँखों में हल्की-सी नमी भी रहती थी। दिल में कुछ घुमड़ता रहता। मौत से जुड़े काम पैसा तो दे रहा था, लेकिन अनजान सी उदासी भी मन में छोड़ देता था।

Today Prakash has sold fifteen packages for the last rites of deceased people. When he finally closed his shop, he had earned a total of twenty-two thousand five hundred Rupees. Yesterday it nineteen thousand. And the day before, fifteen thousand. This was unusual. Before corona, the shop used to sell worth fifteen hundred to three thousand rupees daily. Earlier there would be one or two cremations daily. He would sell for about forty thousand in a month. He would save twenty-five thousand rupees after paying for supplies and the rent. It is true that he has earned well now, but his eyes are soaked with tears. His heart was filled with grief. All this death brought him money but also made him deeply sorrowful.

लकड़ी का इंतज़ाम थोड़ा आसान पड़ा क्योंकि लकड़ी तो उसकी झुग्गी की चद्दर पर ढेरों थीं। उसने लकड़ियाँ खींचना शुरु किया। दो-तीन लकड़ियाँ खींचकर चटक चटक तोड़ी और अपने द्वारा बनाए चूल्हे में रख दी। एक लड़की की प्लाई व गत्ता और रख दिया ताकि लकड़ी जल्दी आग पकड़ ले। उसने आग जलाकर फटाफट तवा रखा और झटपट रोटी सेंकना शुरु किया। तीनों बच्चे उसी के पास अपनी अपनी प्लेट लिए खड़े थे। वे बार बार कहते नहीं थक रहे थे कि मम्मी भूख लगी है, खाना! एक तरफ़ उसके बच्चों की तेज़ भूख दूसरी तरफ़ वो रोटी को बेले कैसे। जैसे ही बेलती उसमें छेद हो जाता। वो बेल ही नहीं पाती। क्योंकि गीता ने ज़्यादा आटे को छाना नहीं था, उसमें जो भूसी थी वो भी थोड़ी ज़्यादा थी। उन्होंने थोड़ी बहुत तो निकाल ली थी, लेकिन अगर वो ज़्यादा निकाल देती तो आटा कम हो जाता।

It was easier to organise some firewood as she had some on the tin roof of her small jhuggi. She took out two or three branches and snapped them in half and then placed them in her makeshift stove. She then placed an old cardboard piece so that it would catch fire quickly. She lit the fire and placed her griddle on it and started making rotis. All the three children had surrounded her with their empty plates in hand. They kept chanting, ‘Mummy we are hungry. Give us some food.” On one hand she could see her children’s growing anticipation while on the other she was finding it tough to roll out the dough. The flour was full of husk. She had tried to sieve some of it out. But if she took out too much then there would be hardly any left to make the rotis. She finally abandoned trying to use her rolling pin and instead used her hands to pat them into shape. She had to make ten rotis. They were five of them so two for each one of them. But she also wanted the flour to last long, so she made the size of her rotis smaller and cooked them on low heat to make them crisp. The rotis tasted so good. In their hunger, no one noticed if the rotis were a little burnt or coarse.